Written by: smac (compound), krane (asula)

Thanks to rajiv, kratik, michael, and thiccy for their thoughtful comments and feedback.

We now live in a world of abundance.

Technology abundance. Information abundance. Capital abundance. Even slop abundance.

But this is a relatively new phenomenon. Back in the early 1970s when the venture industry was beginning to formalize, the environment looked much different. And yet, nearly a half century later, the basic shape created then still dominates today: capital raised in private, prices negotiated in access-gated rooms, ownership locked in illiquid equity, and the IPO as the long-delayed point of public entry.

At the time, both capital and information were scarce. That scarcity made the model coherent: with little public data to rely on, institutional investors depended on a handful of venture firms to source deals, vet founders, and set terms. The gating function of private rounds and public audits ensured that by the time retail investors could participate, the companies were, at least on average, durable enough to withstand scrutiny.

Moreover, illiquidity has long been treated as a governance tool: it ties founders, employees, and early investors to the long arc of building, with liquidity only arriving after product traction, filings, and public scrutiny. That structure tends to produce durable companies, but it also means retail usually enters late in the curve.

Crypto was supposed to overturn that model by offering access from day zero. Instead, in some respects it recreated the worst of both worlds: extractive exchange listings, and billion‑dollar valuations without any semblance of product‑market fit. Liquidity arrived quickly, but distribution, transparency, and durable incentives did not.

In an effort to provide some context, we’ll compare the classic equity lifecycle with the modern token one. We’ll ask what each gets right, and more importantly, what a better onchain capital formation system might look like.

The Equity Lifecycle

Everyone sort of understands the typical lifestyle of equity in a traditional company that ultimately goes public. It’s usually quite long and highly gated. But there’s some stuff around the edges that we think about less, yet ultimately matters quite a bit.

Early price discovery happens behind closed doors, with founders raising capital through angels and venture capital across many, many rounds1. Importantly, price discovery here is based on negotiated terms rather than some sort of open market bidding. Information asymmetry is high and the incentives in this model are generally oriented toward long-term growth, with founders & employees tied to illiquid equity or stock options that vest over many years & cannot be easily sold2. But the core premise is that illiquidity aligns insiders with company success.

Retail investors usually have no opportunity to invest in these companies until an IPO. The criticism of this model is that much of the growth has already been captured by insiders and so the public is disadvantaged (i.e. they are exit liquidity). In some ways, the trend of companies staying private longer only further exacerbates this problem.

The counterpoint of course are companies like Meta. Facebook’s IPO was notoriously a disaster with a shaky roadshow that frustrated a lot of traditional investors. The initial earnings multiple also spooked people who worried about their unproven mobile-ad business and the stock traded down 50%3. In hindsight, it’s clear that skeptics underappreciated a lot of the Facebook story and while early-stage investors benefited handsomely, retail still had an incredible opportunity to participate in the company’s growth. For context, almost any other investment made in 2012/13 is likely to have returned far less than the ~20x FB has delivered since the opening bell4.

Retail access feels especially relevant in a world which is clearly not information scarce and a lot of capital inflow into public markets is direct retail flow:

Below is an excerpt from a recent WSJ interview on IPOs with one of the Co-Heads of Morgan Stanley’s Equity Capital Markets group when talking about IPOs:

Arnaud Blanchard (Co-head of Equity Capital Markets at Morgan Stanley): I think some good performance on the first day is important, and that’s a good sign. Once again, I think people want the good branding and I understand it creates a lot of good media around the name, which is good. Once again, the sophisticated users of our markets and the issuers, they’re more focused on where is it going in a couple of months? Who’s behind and buying? Do I get some really strong mutual funds with conviction, who have the ability to deploy capital over time?

Telis Demos (WSJ): What about retail investors? I know there have been a number of companies like Robinhood and others that have tried to offer investors access to IPOs. But to get into that deal and to participate in that whole process, would you say that retail investors are playing a bigger role in the market now than they were a couple years ago?

Arnaud Blanchard: I would tell you retail is an important part of the success of an IPO for a lot of different reasons. They tend to be big in IPOs, they tend to be early, and they tend to be active buyers in the aftermarket. And so I think those three elements make the retail pool of capital pretty helpful to IPOs, yes.

The reality is that in the modern market regime, retail is one of the largest sources of flow. They have fairly predictable behavioral patterns5, but one of the most important ones is their tendency to prioritize narratives over all else. This is not necessarily a criticism but rather some necessary context as we see the tradfi and crypto worlds colliding more and more frequently due to the nature of information propagation on the internet.

So to summarize briefly, the equity lifecycle has been characterized historically by

- delayed price discovery

- long-term aligned incentives for insiders albeit with very limited public access

- restricted liquidity

- high regulatory bar6 (not something we mentioned but is a known reality)

Token Lifecycle

Ok now let’s take a look at token lifecycles:

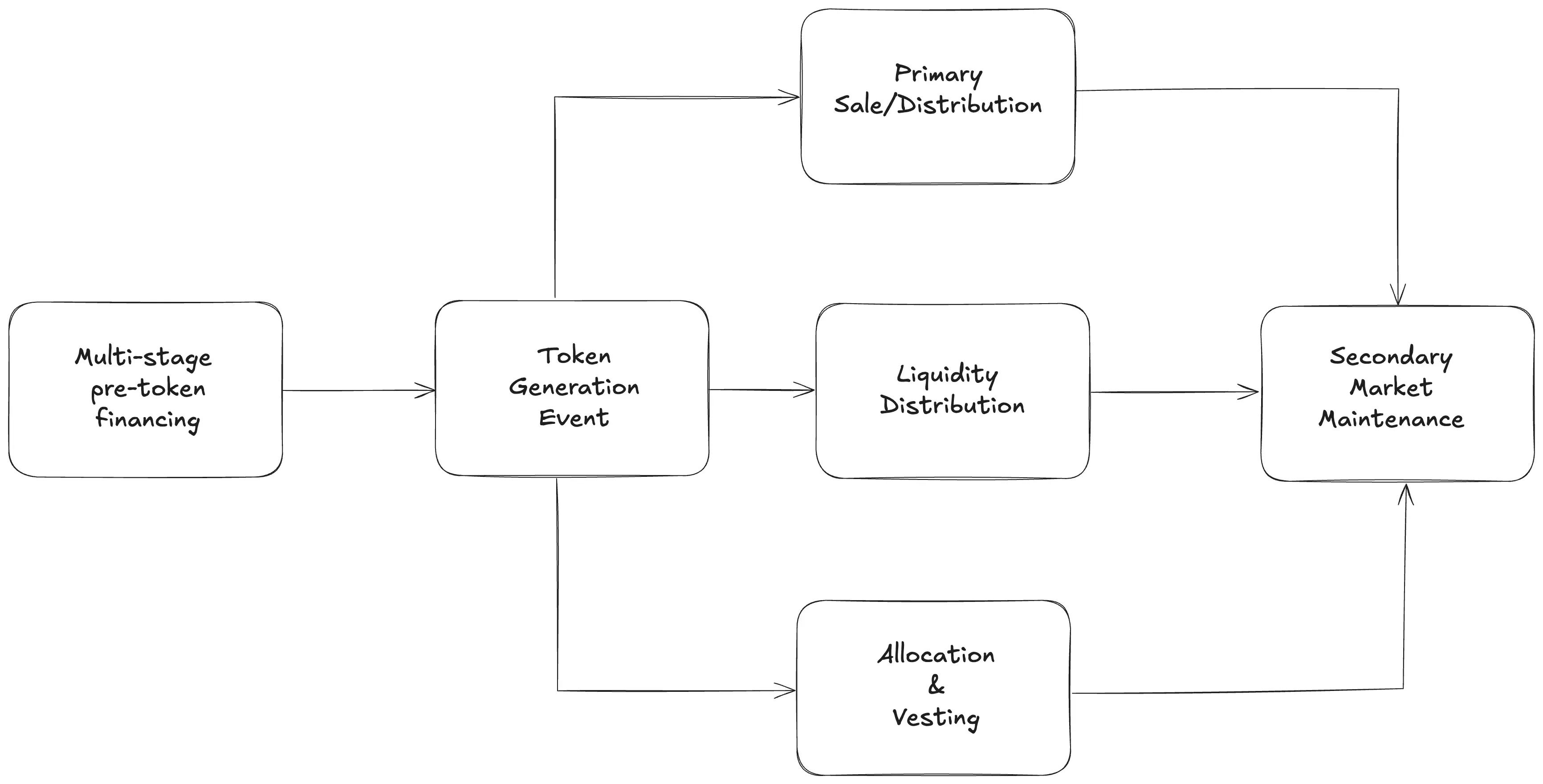

Token Lifecycle

Today it is objectively true that in general more of the price discovery for tokens is happening in private than previously (pre-token financing). Cobie wrote about this last year, but this phenomenon has been understood by many market participants for years. Seed round allocations were often seen as “free money” since protocols would normally go through several rounds of funding before TGE and be so hyped on TGE that they would never drop below their private valuations (let alone get to their seed round valuations). However, this line of thinking also led to an oversupply of tokens, most of which were uninvestable7.

The reality is that price discovery for tokens is far more front-loaded and continuous than equity. Yes it’s true VCs and insiders set the price in closed rounds early-on, but open market bidding also happens much earlier in the project lifecycle. Smac’s written about this before, but in some cases we see tokens launch and get listed on centralized exchanges before achieving any semblance of product-market fit. While TGEs aren’t like IPOs, exchange listings that give tokens a distribution channel to tens of millions of users are akin to IPOs. Listings open up a completely new source of financing for these tokens. Early liquidity is a feature, but it complicates incentive alignment and in a lot of cases discourages long-term, empire-building at the company level8. Because liquid markets exist so early on, founders and early employees have a visible perceived value of their stake immediately. If the perceived value is high enough, naturally these people will begin thinking about how they can take chips off the table. Pretending a chart that dictates one’s net worth doesn’t affect human behavior is ignorant – teams and early investors can be tempted to cash out sooner, fixate on short-term token price and actively make decisions that benefit insiders around unlock dates9.

This also doesn’t take into account the active secondary market for tokens, both pre and post launch. These decisions have an outsized impact on the durability of projects long-term; shallow trading liquidity plus speculative market whims means the morale and resources of a project can swing wildly even as v1 of the project is launching. But liquidity is clearly valuable or investors wouldn’t trade loss ratio in exchange for lower returns (i.e. liquidity has an implicit premium: people will “pay” for it by accepting lower return expectations).

Until recently the token lifecycle has operated in a regulatory grey area. This has changed in some jurisdictions, is changing in others, and will ultimately change for any market that intends to be relevant moving forward.

In short, historically the token lifecycle has been characterized by

- Fast, early & continuous price discovery

- weak long-term alignment

- less restricted liquidity for insiders

- high asymmetric information skew even when publicly tradeable

A big frustration is that the market is willing to accept the novel challenges tokens introduce, specifically managing short-term market forces and early liquidity. But it’s only willing to do so if the token lifecycle actually democratizes access to investment and allows participation. The second half of this equation has been largely corrupted and existing market structure around token launches has played a huge role in that.

No CEX is better than bad CEX

DeFi promised disintermediation and yet the reality is that centralized exchanges control retail user relationships and thus token price discovery. It was true that in the past CEXs provided real value to teams, and were at least a tacit stamp of legitimacy approval. But in 2025 reliance on CEXs has real costs, both direct and indirect; in many ways the last few years have pierced the veil to show how extractive they can be to token projects and how distortionary they can be to incentives.

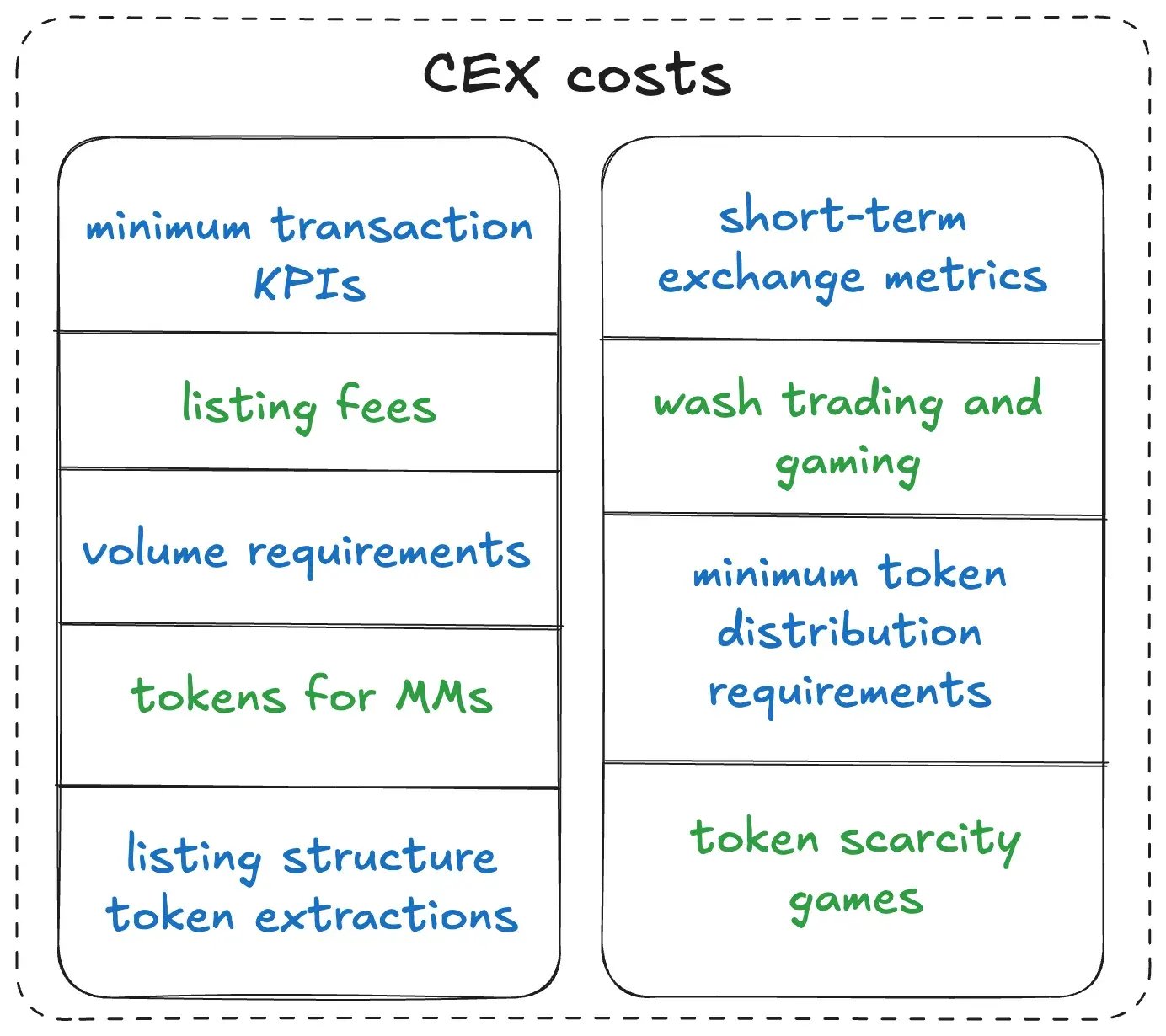

CEX Costs

CEXs are fully aware of their gatekeeping power and use this leverage to charge projects enormous fees and impose severe conditions in order to get listed. In many instances those conditions lead to awkward design incentives that kneecap long-term health and growth. There’s also an adverse selection problem here where teams willing to pay most for CEX distribution tend to be those optimizing for short-term games.

Direct costs

Assuming a team is able to navigate what is often a fairly opaque labyrinth, the reward at the end is a pound of flesh for a listing. Conservatively speaking, the team sacrifices 7-10% of total token supply in listing & liquidity fees. These fees are extractive in the purest sense – they are value that could have gone to project development, growth, hiring or community incentives but instead become a cost to access liquidity. Some will say “this is a worthwhile cost to get liquidity” but that’s only true if there’s no alternative. What this also potentially does is keep the loss ratio up: the token doesn’t teleport to zero and thus becomes “lindy” around some market cap for long enough that it just bleeds forever rather than launching directly into a $0 sell wall. If the job of a CEX is to connect willing buyers to the best/most interesting tokens then the listing criteria probably shouldn’t be direct payment. The bare minimum should be transparency.

On top of this, exchanges require that projects commit to providing liquidity through designated market makers. What does this mean in practice? A chunk of tokens are given to market making firms as inventory (or payment) to tighten spreads and maintain adequate order book depth. This is a pseudo hidden tax because it means projects without sufficient backing struggle to meet this demand and so the market distorts toward only well-funded (i.e. VC-backed) tokens reaching top exchanges, reinforcing a cycle where insiders dump on retail.

There’s also the perverse incentive to design the token and token launch in ways that actively encourage volume trading over all else. Low velocity of token trading means lower fees for the exchange listing the token (and thus, less incentive to list the token in the first place). One way to avoid this problem is incentivizing specific short term behaviors that lead to higher token velocity at the expense of long-term health.

Beyond these direct costs, the centralized exchanges have also evolved to extract in subtler ways through listing structures. Some examples here are the IEOs that became more commonplace since ~2019 which allowed exchanges to run token sales on behalf of projects, typically for a token fee or a % of raised capital. In a sense, teams using this were paying exchanges for both the listing & for fundraising brokerage services.

Indirect costs

Arguably the indirect costs are even more destructive to long-term sustained success. The obvious major distortion is the heavy pressure to focus on short-term exchange metrics. Teams trying to get listed on major exchanges feel pressure to maximize trading volume since CEXs naturally prioritize high-fee generating assets. The egregious wash trading and fake volumes we see in crypto are directly downstream of this as projects either engage in or tacitly encourage this type of behavior in order to appear more attractive to exchanges. Rather than building real utility or focusing on the product, teams are allocating resources to market-making gimmicks that simply create the illusion of activity. An unfortunate second-order effect is that real teams end up distracted by this stupidity while teams without a real intention of ever building anything valuable end up being the best token pumpers. This is all tail-wagging-the-dog nonsense.

Tokenomics are another soft distortion that we see frequently with CEXs as teams try to cater to different exchange listing rules, and in some cases game retail interest once listed. Some exchanges prefer tokens with wide distribution minimums which can drive teams to do large indiscriminate airdrops just to meet some arbitrary holder count. There’s also been incentive to keep circulating token supply artificially low at listing in order to create scarcity narratives and use numba-go-up tech as a marketing tool for uninformed buyers. There are also countless examples of short-term vesting deals with market-makers or exchanges themselves which allow insiders to get tokens early or at a discount to help “provide liquidity” at launch. In reality this is just a proxy for these entities to profit as the token launches which only perpetuates the mistrust and feeling that CEXs promote an insider trading environment antithetical to crypto’s original promise. We’re sure there will be market-makers who disagree with how they’re being portrayed here but the reality is that the ones acting in good faith should be equally as enthused about bringing transparency here.

All of this is just capital structure malpractice10 and is downstream of gaining access to the distribution and liquidity that CEXs have enjoyed for years.

Today’s market structure is optimized for tokens with a half-life of weeks, if not days. Until market structure for tokens improves meaningfully, we can’t expect other deep tech sectors to use onchain protocols and infrastructure for capital formation, listings or secondary market liquidity.

However, not everything is doom and gloom. There are meaningful silver linings.

A path forward

Say what you will about the pumpfun token but its launch gave a peek into what the future may look like. First, the pump team was able to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in minutes. This directly shows the potency of onchain capital formation. Moreover, rather than immediately listing the token post-sale (which many ICOs before have done) pump employed a multiday distribution phase that acted as a sort of volatility control mechanism. Staging it this way allowed them to create some type of orderly market entry and allowed exchanges to prepare infrastructure to make the launch more synchronized.

But what was perhaps most exciting was watching in real-time as the future of capital markets flashed. We saw premarket perps launch before spot trading began, and the magnitude of premarket trading11 that Hyperliquid supported was especially revealing. We then saw the pump token launch go off largely without a hitch as Solana was able to support it, continuing to pack full blocks with the median fee spiking to just 2 cents. Solana and Hyperliquid together accounted for most of the spot volume for pump, with Hyperliquid becoming the venue for both spectators and speculators to follow/participate in the launch.

Pump Token Launch and Onchain Price Discovery

It felt like a “holy shit” moment for some who’ve been cynical or skeptical about the progress and direction of crypto. What was most impressive was that price discovery was happening onchain. This is insanely powerful and has massive implications if it becomes the norm. True price discovery venues ultimately become the primary reference for institutional order routing, index construction, derivatives and an almost infinite list of other important market structure dynamics. This is because price discovery implies organic flow that wants to express a view and take directional bias. Institutions want to participate in markets where they aren’t constantly in a knife fight against their market making counterparts. This is the real promise of crypto for a lot of people – capital formation and the ability to transact permissionlessly with in-demand assets. The “in-demand assets” part of this equation cannot be understated, especially as the world moves toward shorter attention spans, higher volatility and quicker trade lifecycles.

While this potential inflection point suggests we’re hurtling toward an onchain future quicker each day, it still relies on the evolution of emerging token launch infrastructure, so let’s explore what the stack could look like.

It’s worth calling out specific parts of this stack and some of these are more feasible in the short-term than others for obvious reasons. Is it likely we see SAFE/SAFT transparency that become freely tradeable in the near-term? Doubtful.

ICOs

But there are several meaningful steps that can be taken as teams approach and move past the TGE of their protocol. First, ICO style raises for products with real PMF feels like low-hanging fruit that the market is screaming out for. If ICOs can be structured to give real and early users of protocols/products the capacity to get skin in the game using onchain data (or using some version of zkTLS for offchain data), this seems like a strict benefit over paying tithes to CEXs for distribution. As we’ve seen from the success of Hyperliquid, the decentralized marketing machine of stakeholders can achieve a very large amount of attention capture if incentives are correctly aligned.

Cap Table Managment

Cap table management software must be able to cross the offchain <-> onchain chasm. If SAFEs, SAFTs and token warrants are managed on the same platform as tokens, we could ensure full cycle fidelity of ownership and also allow teams to make transparency disclosure with the click of a button. Blockworks is currently spending a ton of time working on a transparency framework12 and we have the technology to make team token addresses visible today. There’s no reason that cap table management can’t be moved completely onchain as well – this is mostly a legal barrier as opposed to a technological one.

You can imagine a world in which any individual holder above 1%13 of token supply is automatically added to a public cap table system. There are feasible avenues to allow for participants to understand what the full cap table looks like at any given point in time – we can use privacy technology to obfuscate identities but these are the types of table stakes improvements we need to see.

NB: Gavel, by the Ellipsis Labs team seems to be a product expressly aimed at the ICO style capital formation and onchain cap table management.

TVL Raises

Private TVL deals are another extremely opaque feature for the wider public. The largest capital providers (market makers, funds, whales or HNWI) know they have leverage over projects who don’t want to launch with $0 TVL on day 1 and are oftentimes willing to provide overly advantageous terms as an incentive to inflate vanity metrics early in the project’s lifecycle. It’s effectively a rental fee for capital which more often than not is just an expensive way of putting lipstick on a pig. The actual terms and deal structures vary but these parties generally demand preferential yield paid in stables and usually juiced with native token incentives that, if we’re being honest, is at-best a marketing expense (“ooo much TVL, good project”) and at worst a deceptive tactic to knowingly fleece retail. These TVL renting structures still follow the exact same black box format SBF described in his Odd Lots interview with Matt Levine back in 2022 which obviously did no favors for the perception of DeFi protocols amongst the wider finance community.

Plasma recently used Sonar (by Echo) to bootstrap TVL by allowing pre-mainnet depositors to the Plasma L1 the opportunity to buy tokens pro-rata at a FDV of $500m. Given the success of the program and the general exhaustion of the community with opaque TVL deals we expect more protocols to opt-in to bootstrap TVL through more transparent models like Sonar.

Market Making

As previously mentioned, CEX listings often come with the requirement that teams pay market makers to keep spreads tight. In order to do this, market makers often borrow tokens from the treasury for 12-18 months and provide liquidity on exchanges. However, due to the opaqueness of these deals along with the offchain nature of CEXs, no one really knows what’s happening. There have also been public instances of malpractice from some market makers that leads to a natural demand for greater transparency.

If onchain venues become the main mode of distribution of tokens, smart contract vaults can allow professional market makers to borrow both tokens and stablecoins to provide liquidity to markets in a constrained manner. The vault could naturally prevent the movement of tokens to another address and can also limit the smart contracts that the vault can interact with. Moreover, any misbehavior would be completely onchain and subject to scrutiny by the wider community. In fact, HIP-2 is an implementation of this exact system with a static strategy. As a token grows, the static strategy can be replaced by active/professional yet auditable market makers.

All in all we believe that if we can avoid the more extractive, distortionary and opaque CEX listing game, then the long-term viability of projects should increase and we should see both higher success rates and larger outcomes14. The other added benefit is that it’s easier to distinguish the best teams from the ones just looking to rip as much money out of the system as quickly as possible. So long as the infrastructure is there to support them, people willing to go through the scrutiny of a transparent, fairer system signals something about their intentionality compared to those just looking to play a smoke & mirrors game.

On top of that, less tokens designated to extractionary activities implies more tokens for those that work to make products successful: the team and the users. But how do we reward users?

How To Reward Early Users/Participants

Rewarding those that believe in a product early is not a unique idea. Investors back companies with capital and get rewarded for it. Employees at companies contribute their time to the product and thus, get rewarded for it. Users of financial products take meaningful amounts of capital risk by using new products, and thus should be rewarded for it. In fact, even users of non-financial products chew glass and go through meaningful amounts of feedback cycles with teams and might deserve to be rewarded.

In an ideal world, product/protocol users would be able to buy tokens at privileged prices and in our opinion this is the truest form of the ICM meme. Instead of bulk, indiscriminate airdrops which are almost always capital inefficient, users should have the ability to purchase tokens at a discounted price based on activity. However the team wants to define the activity they find most valuable to their underlying protocol or application is fine – but toggling the price15 and/or quantity available for purchase on a wallet-by-wallet basis helps differentiate how valuable the activity is.

Concluding section

There is a clear drag on the space today because of the state of token market structure. There’s an objective hard, quantifiable tax (i.e. % of tokens that go to CEXs, dollars and tokens that go toward market-maker deal sweeteners, % of tokens that get sybil farmed, % of tokens that go to bootstrap liquidity providers) but also a softer, harder-to-quantify drag (i.e. decisions that teams are forced to make with limited resources). Giving away 10% of your token supply is not just a $ figure issue but it also has negative implications on how you can fundraise, incentivize employees or hires, the metrics you need to bend the company to focus on in order to get listed.

The CEX-first launch made sense when onchain infrastructure couldn’t keep up with the performance latency, depth of liquidity or overall UX. But that gap is quickly closing thanks in large part to Solana becoming extremely mature as a launchpad for spot assets and Hyperliquid’s success in providing CEX-like derivatives liquidity onchain.

However, onchain venues are still somewhat distribution constrained. Phantom, which supports both Solana and Hyperliquid has ~10m monthly active users, is still a long way from Binance which has >200m users. While supplanting the distribution of centralized venues may seem like a challenge today, we expect innovations like builder codes and the HIP stack to encourage many builders to focus on distribution and unique assets as opposed to re-building the same financial infrastructure we’ve been building over and over again over the past 10 years. As distribution for onchain venues and the nature of the flows becomes more durable, it’s feasible that the question of “When Binance listing?” shifts toward something more like “How do we maximize our onchain launch?”

The largest winners here will be those who no longer treat their token sale as a single event (exit liquidity) but rather a programmable, evolving economic system that lives entirely on-chain from day 1.

Footnotes

-

We also know companies are staying private longer in part because of the institutionalization of the biggest venture firms. ↩

-

Again this is changing as the private markets become more institutionalized, including the secondary market. ↩

-

The opening price for FB was at $38 per share and it traded at $18 per share within a few months of launch. ↩

-

$META sits at $739 at the time of writing ↩

-

A whole separate post tbh ↩

-

This regulatory bar makes it possible for retail to bid with some implicit bounded risk – or at least that is part of a soft social contract, though how real that bounded risk is is up for debate ↩

-

This did not stop funds from investing ↩

-

Scope of ambition remains one of the rarest traits for crypto founders today and if you think about all of the most successful teams thus far, each of them is always thinking about how they can continue to simultaneously grow the pie and land-grab ↩

-

A favorite trick to play is trapping shorts ahead of an unlock date by announcing a re-lock or delay that gasses your token higher temporarily ↩

-

Another example of this was the absurd ability for insiders to sell staking rewards while their tokens vested ↩

-

$400M in OI & >$600M in 24H volume ↩

-

This is a start but doesn’t prove or disprove the existence of side letter deals that let participants express risk in another way ↩

-

1% is just an arbitrary number ↩

-

in theory ↩

-

legality of this specific point is unclear in the US as there are conflicting beliefs depending on how tokens are classified ↩